Microbiome ecology

All animals have evolved in a microbial world, and are colonised on internal and external surfaces by a complex community of microbes. What’s more, we now know that these microbes are not merely passengers, but that many hosts, especially vertebrates, rely on their symbiotic communities for key biological functions. Microbially sterile vertebrates have a range of impairments, indicating that they need at least some microbial symbionts to function normally.

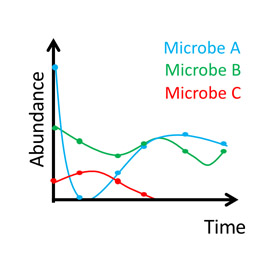

Yet, despite their apparent importance, these symbiotic microbial communities show tremendous natural variation – showing pronounced within-host dynamics and varying consistently among hosts within any given population. What then, is the significance of all this variation in these supposedly critical communities?

Two key questions we ask in the lab are:

- How and why does natural variation in the microbiome arise in wild animal populations?

- What, if any, significance does variation in the microbiome have for host fitness?

By tackling these questions, we aim to shed light on what role the microbiome might play in host adaptation, the extent to which hosts can control these communities, and how host-symbiont relationships may be affected by environmental change.

For much of this work, we utilise population-level studies of wild rodents and their gut microbiome as model systems – wood mice in Wytham Woods, and wild house mice on the island of Skokholm, while dabbling in other study systems, such as birds and fish, too.

-

Microbial transmission ecology

Most gut microbes are gut specialists, acquired from other animals via the faecal-oral route. However, the transmission ecology of gut microbial symbionts in nature remains poorly understood. What kinds of interactions promote the sharing of gut microbes? How... Read more -

Drivers of microbiome variation

Among individual variation Within a population, individuals usually show marked differences in their microbiota, and these are often repeatable over time - the microbiota can be highly individualised. But to what extent are such differences determine... Read more -

Phenotypic effects of the microbiome

Microbiome variation is frequently said to have critical effects on host fitness. While it is clear that having some microbiome (rather than none) is clearly important for host health, and that changes in microbiome composition can affect health-related traits... Read more -

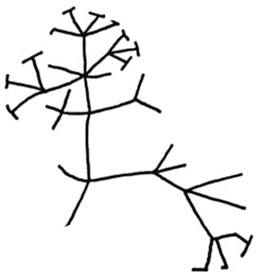

Phylosymbiosis

Different host species often harbour characteristic symbiont communities. Moreover, in some animal groups, ‘phylosymbiosis’ has been observed, whereby symbiotic community composition mirrors the host phylogeny. Recently, we showed that host phylogeny do... Read more